Primary Audience: Production

Site Tags: Filmmaking, Mental Models

Why I'm writing this

Over the course of recent months, I’ve seen a number of folks take the position that the film production slowdown was caused by the strikes. Typically these assertions are informal, indirect, or disgruntled. Seeing this this type of conjecture surface repeatedly, I thought it worth weighing in.

The idea that the 2023 Writers-Actors Strikes caused the production slowdown is wrong. Frankly it's simplistic & reactionary. Crediting the strikes as to causing the slowdown is akin to crediting day-old bananas for birthing fruit flies. Yes, these events happened in succession, but that does not mean one spawned the other.

What was happening in the world of TV & Film Production prior to the strikes wasn't tenable to sustain long-term. It wasn't being reinforced by market drivers, rather it was a product of misplaced competition happening at a macro level.

In this piece I’ll explore & connect two phenomena. Both of which together contextualize today’s state of TV Production.

1. Category Creation via Subsidization,

2. The Nash Equilibrium of TV Production

Caveat: There is a dual slowdown happening in the Commercial Production World. This piece will not focus on that. And although this Nash may offer secondary or third cause explanations, commercial production changes can be better attributed to disruption in the advertising written about here.

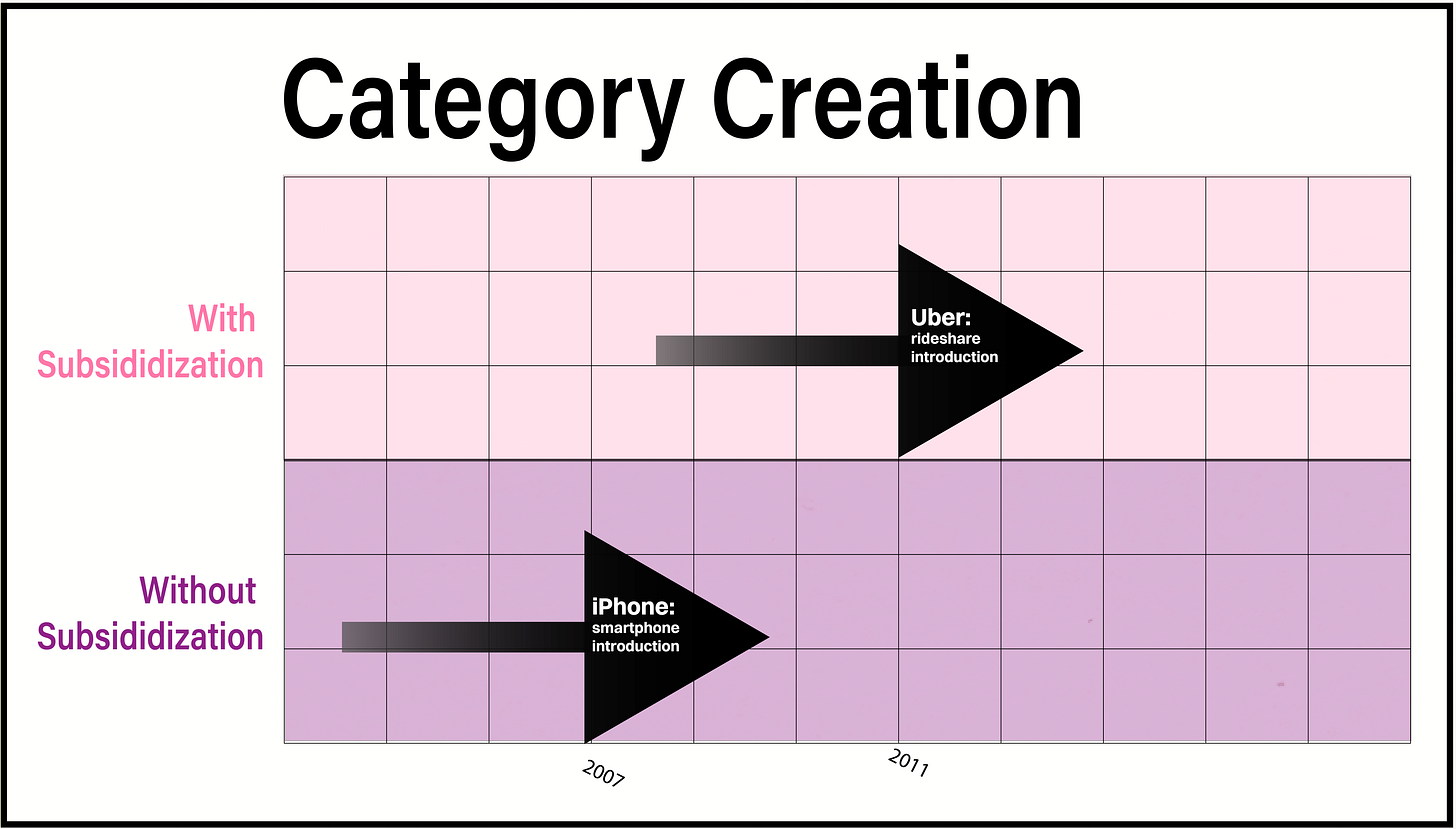

Category Creation via Subsidization

Category Creation via Subsidization. Let's break it down, what is it?

Category Creation: creating an entirely new category of product. One that the consumer has limited or no familiarity with.

Subsidization: subsidization as a business strategy pertains to giving up the profits of short-term dealmaking, to favor those of long-term position. It means to effectively operate at a loss for the purpose of generating repeat business. Doing so requires heavy upfront investor-capital spend, hence the term subsidization.

Taken together, what do they mean?

Category Creation via Subsidization: when a consumer is faced with a new market category so unfamiliar it requires the deal be extra appealing to lure the consumer in. This is made possible via subsidization.

Done effectively this type of category creation embeds itself into the consumers life & culture. It becomes established social practice. And it creates dependency, where once there was none before.

After consumer dependency is established, the bargaining position of the company is advanced to the point it can re-negotiate the initial terms service.

Before exploring what happened in TV Production, let's look at a prototypical example of what this practice looks like in theory.

The Uber Example: the secret trial period

Everyone knows what a trial period is. A temporary period in which you procure a service at low or no cost. One way to understand how category creators operate at these outsets, is to think of it as employing a secret trial period.

A trial period that's not disclosed as such. One in which the service will come across as delivering more value than it may rightfully be able to do. But in this case the consumer isn't an individual, but the entire market in which it operates..

The Components of a Rideshare Service

[Riders] → [Uber-app] → [Driver-service]

The challenge for Uber was two-fold.

1. Starting from a zero network effect, i.e. the cold start problem. It would need an immediate network of Riders & Drivers to simultaneously exist at scale. And..

2. The current customs and norms existing in the social fabric preventing consumers from engaging with the unknown.

Subsidization is the secret sauce in the mix here. By subsidizing and subsidizing big, it was able to scale a mass user & worker network at speed →

By offering riders affordable deals and offering drivers "very" profitable incentives, Uber was able to instantiate itself into existence.

And hence Uber entered the lexicon and became established social norm. Years after becoming accepted practice, it began renegotiating the terms of its service with riders & drivers alike. Today it’s considered a prime example of how this growth via subsidization strategy can lead to profitability.

The Netflix Example

Similar to Uber Netflix introduced a new consumer-category, streaming. Or perceived at the time as internet TV. In an effort to make it's product as appealing as possible, it had to employ a subsidization strategy. Invest big + aggressively.

At a baseline it had to offer exceptional content, but it would have to go a step further to shift consumers from other providers.

It had to be A LOT of content.

It had to be inexpensive for the consumer.

And it had to be commercial-free.

In a heavily competitive market, this kind of subsidization required paying through the nose. Leveraging tremendous debt, Netflix ingratiated itself into the culture.

Fast Forward 2018

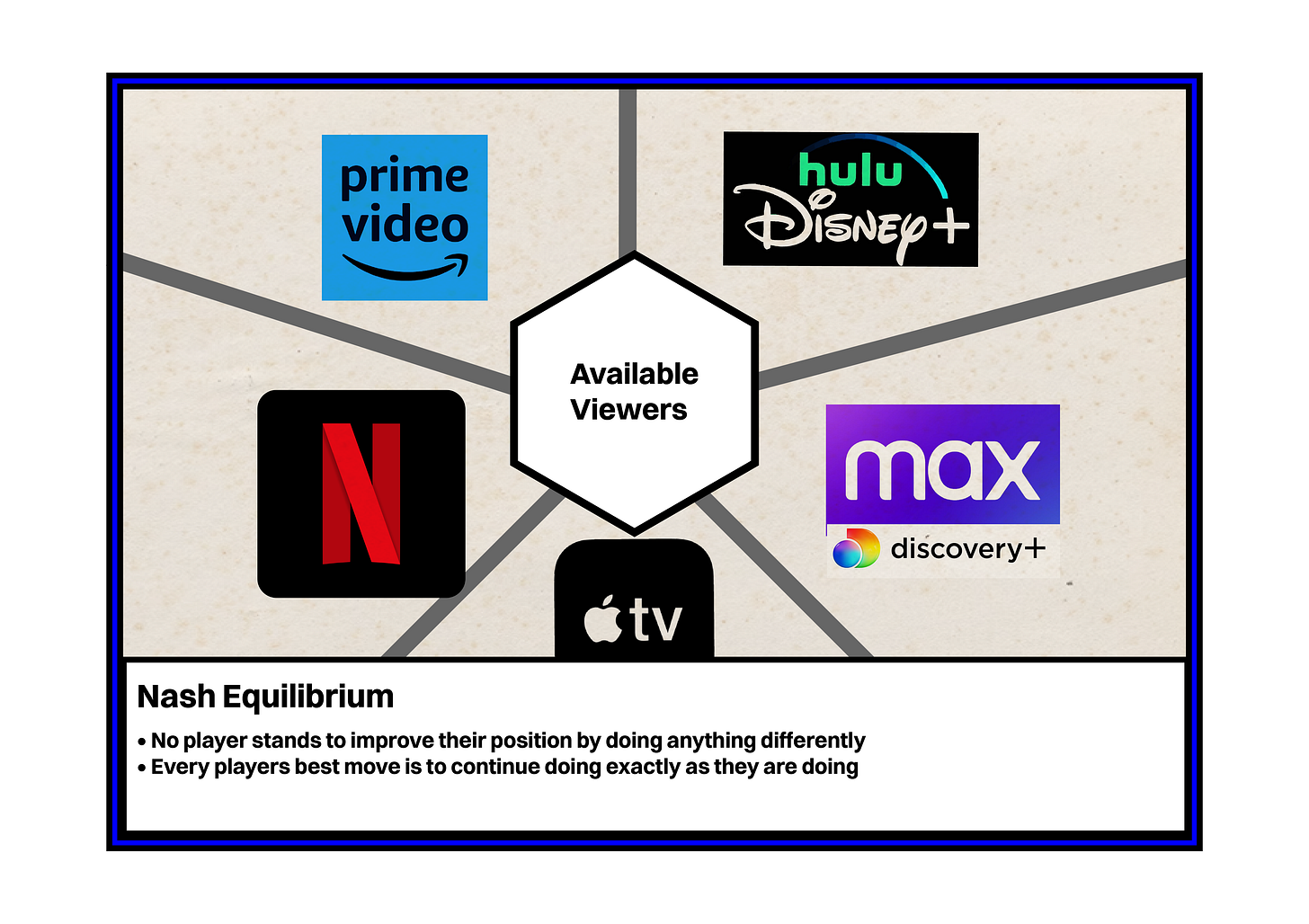

Competition via Subsidization (i.e. madness)

Fast forward to 2018 and Netflix is no longer a lone-operator selling its Streaming-Wares. No, it is an incredibly competitive market. And just like Netflix, its competitors have decided to use the subsidization of their business as a means to compete.

Everything Netflix did is clear to me. I understand where it started, where it wanted to go, and how it was planning on getting there. What remains continuously elusive to me is: what were its competitors hoping to gain by mimicking its tactics without mimicking its strategy.

For whatever reason, top streaming platforms decided that their best approach to competing with Netflix was to do so voluminously and with the leverage of their own debt.

When we talk about volume and spend, what we are talking about is Film Production. By 2018 all major streaming companies were producing record amounts of Television Shows, and Platform Movies.

Each platform was attempting to use its ever-growing libraries to lure audiences away from the next platform. Each platform was also becoming ever-more invested in its own commitment to competition (despite minimal gains and higher stakes.) John Nash created a great framework for this exact type of situation.

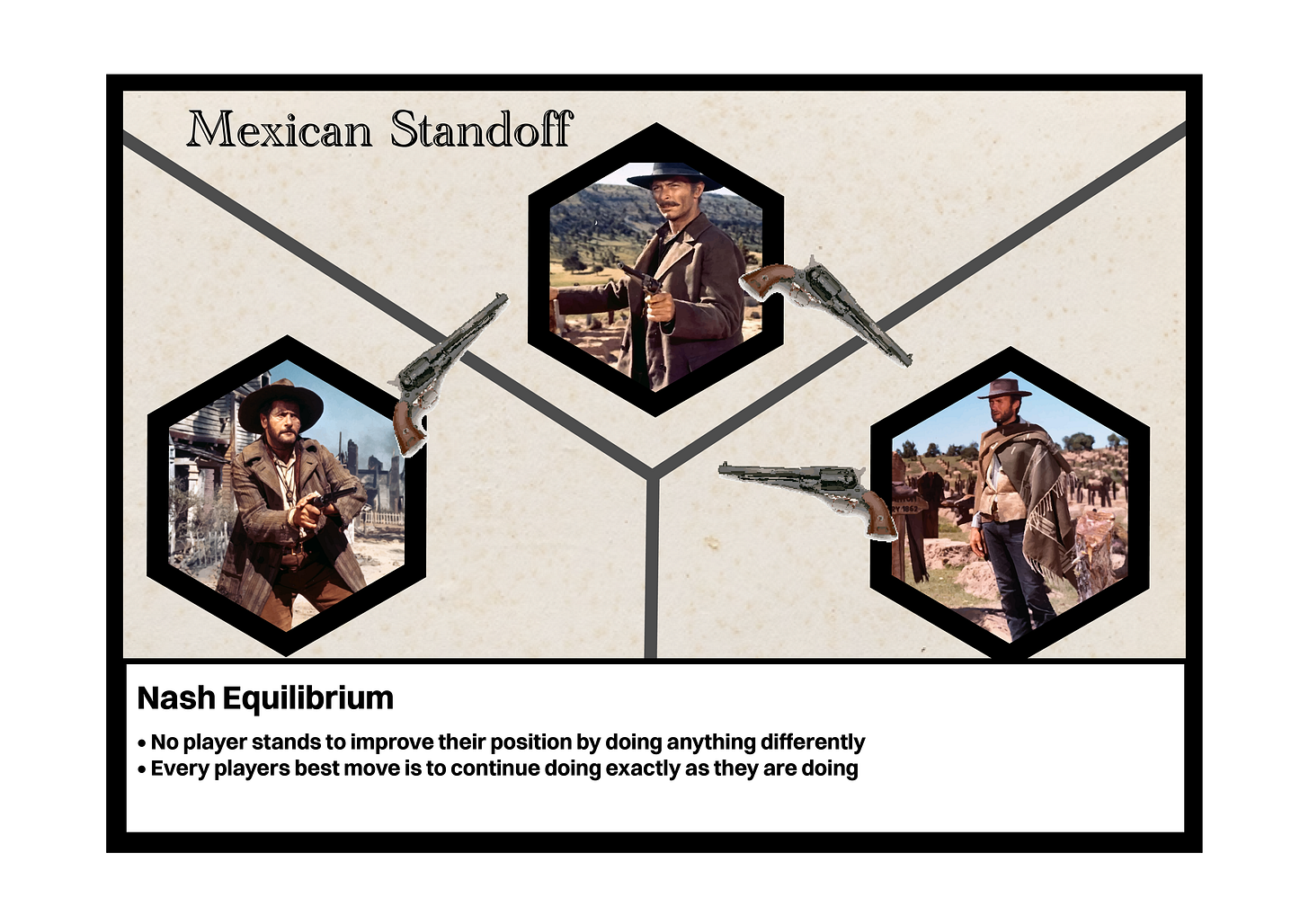

Nash Equilibrium

What is it

A Nash Equilibrium is a situation in game theory, in which all competitors reach a point in which none of them can advance their position any more than they already have, and should they make ANY CHANGE they will suffer loss.

This can be better understood as a Mexican Standoff.

Other examples of Nash Equilibriums:

Traffic Scenario:

Driver on the way home from work is taking Route A. Alternatively Route B is 6 minutes faster. However given that it is rush hour, the cost of switching routes is likelier to cause more delay than benefits. Therefore the most effective decision for Driver to make, is to continue on current route. They are in a Nash Equilibrium.

Cold War:

During the Cold War both players (US, Russia) pointed stock piles of nuclear warheads at the other. Neither stood to benefit from changing their current positions. Other positions being: attacking, de-arming, increasing nuclear warheads, decreasing nuclear warheads. Both players best strategy was to continue doing exactly as they were, ie a Nash Equilibrium.

Netflixian Standoff

From the periods of 2018 to 2022, the top major streaming companies competing for streamers were producing TV and Movies at an all-time high. Netflix was doing so to maintain market dominance, and competitors were doing so to claw back legacy viewers.

My view is that regardless of how they arrived at this interception. Each player was committed to the point of loss aversion. The view being, should they stand down from Production they will suffer immediate + long-term viewer loss. Only by providing plentiful content options to viewers, ie TV Production, do they stand a chance to keep or gain viewers.

This position of competition in fear-of-loss was self-sustaining unto itself. Then the 2023 Writers & Actors Strike's happened.

The Strike that broke the Nash's back

The strikes inadvertently forced a pause to all new content, and in essence the competition itself. It was effectively as if a referee called 'Halt!', and allowed the pieces (viewers) to fall where they may. In the 6 months it took for the strikes to end, the Nash Equilibrium was no more.

For a Nash Equilibrium to function, it is contingent not just what on the stakes are for the player, but it's contingent upon every other players position on the board as well. For there to be a Nash Equilibrium, every single player must be caught in a deadlock, for fear of moving, given the next player's position.

If it wasn't the Strikes it would have been something else

A Nash Equilibrium cannot go on forever. Nash Equilibrium's are typically broken by external events. In macro economics these events could be market entries, economic shifts, cultural trends, all of which can end an equilibrium.

Other examples of Nash Equilibriums (ending):

Traffic Scenario:

In the aforementioned traffic scenario the implementation of congestion pricing, makes travel on both Route A and Route B more expedient, allowing Driver to switch to the more optimal Route B without the cost of delay. This is an external shift brought on outside the driver's control.

Cold War:

The political + cultural shifts that occurred across Eastern Europe in 1989, lead to the Fall of The Berlin Wall, and the eventual dissolution of the Soviet Union(1989 to 1992). Effectively breaking the Cold War Nash Equilibrium. This is an external shift that happened outside any of the players control.

The truth of it all

If it wasn't The Strikes something else would have ended the untenable position of high-volume TV Production occurring amongst streamers. Be it by bankruptcy, shareholder demand, conglomerate absorption, or unknown-unknowns. Something would have broken the standoff.

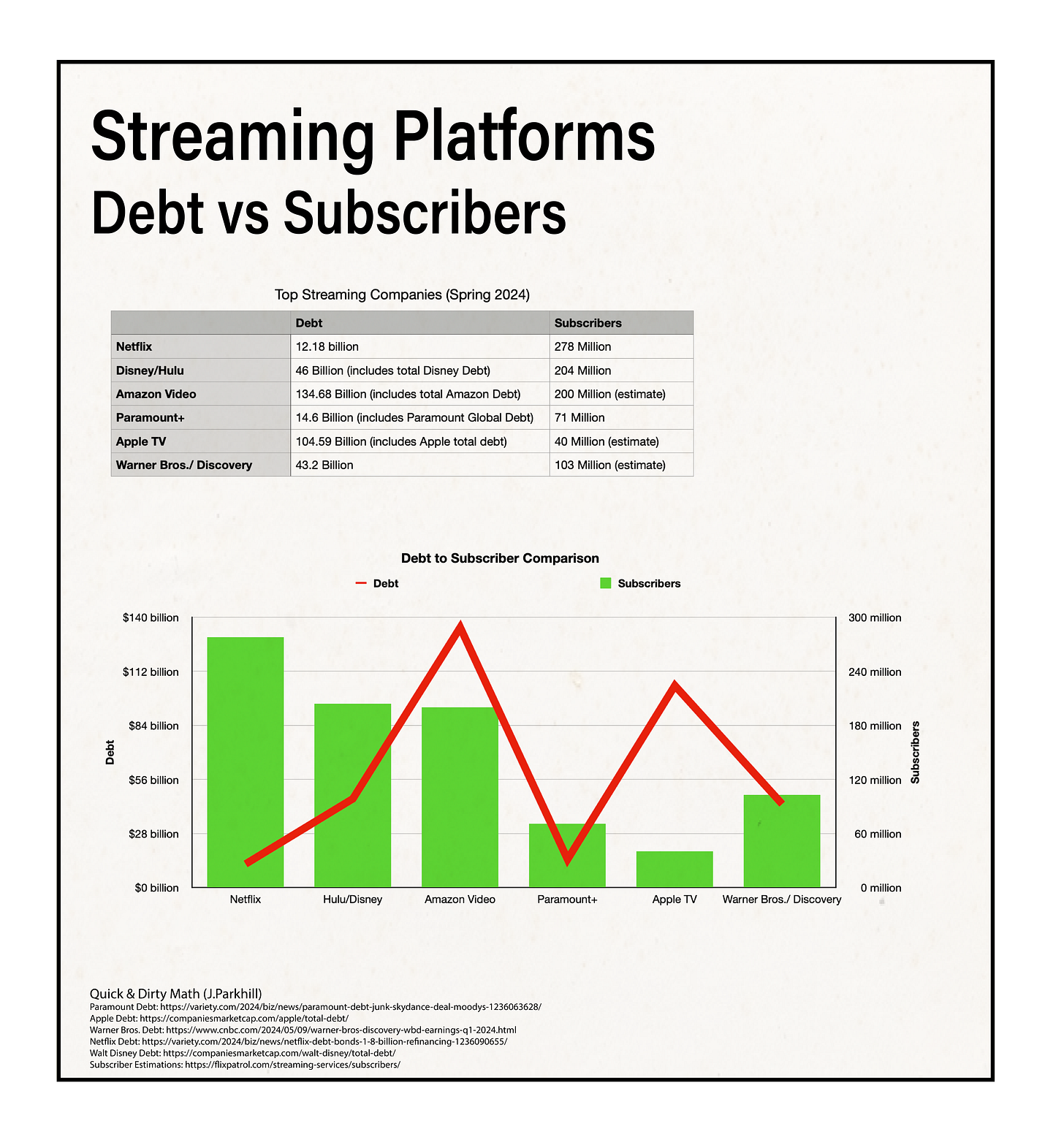

In 2022 the cost of Hulu was $8.99 and the cost of Netflix was $9.99. The amount of content being given to the viewer for $9.99 was not enough to justify the cost of every production crew in NY & LA working to generate said content.

Afterthoughts

To the Victor goes the Spoils

The victor of the subsidization strategy is the category-creator themselves, Netflix. Dubbed as much by a ubiquity of publications across the land, and after doing some quick & dirty math myself, it all seems to add up. Using imperfect google data, it’s obvious Netflix is doing far better than any of its competitors when it comes to subscriber count + debt.

Market for Production Today

Less Consumer Value

The most duplicitous rub here is what resulted from this hyper competition is the value of Production Content itself became diluted. Meaning, the expectations of the consumer have been raised to an unrealistic standard.

Furthermore, a category predicated upon 'No Commercials' has disallowed itself the revenue stream Cable TV was built on. Relevant because Cable TV in it's Prime produced similarly large amounts of content to streamers today.

Note: Efforts are taking place to walk consumers expectations back, but they are still "not material" in a fiscal way, at present.

Victory without Market Dominance

Looking back at the strategy ride-share apps employed, Uber and Lyft were both able to achieve shared market dominance. And in doing so were able to renegotiate the terms of the market with (with both drivers and riders).

Unlike Uber & Lyft, Netflix was not able to achieve market dominance, that is despite being the category-leader. Netflix nor any other major streamer has the consumer clout needed to renegotiate it's value.

For instance, should any platform either:

A) Set it's user fee to a more realistic amount. (One that would actually pay for the content being generated, say $30 a month.)

B) Employ a more realistic amount of commercials, to offset cost.

Than in doing so, surely a Tragedy of the Commons scenario would occur. The next competitor would step in, undercut them, and draw consumers away.

Foot Thoughts

Phrases (I think I coined)

Quick and Dirty Math: Marginal. Rule of thumb. Good for the purposes of working-estimation. Never to be laden by the burden of precision.

Other Phrases:

• Category Creation via Subsidization

• The secret trial period

Fun Reading

+ Network Effects Bible [web]

+ The Incentive Structure of Television [Frame by Brand]

+ A Beautiful Mind [book] [audiobook ]

Notes

‣ The title card is purportedly misleading. No, I do not attribute John Nash as to causing the Production Slowdown.